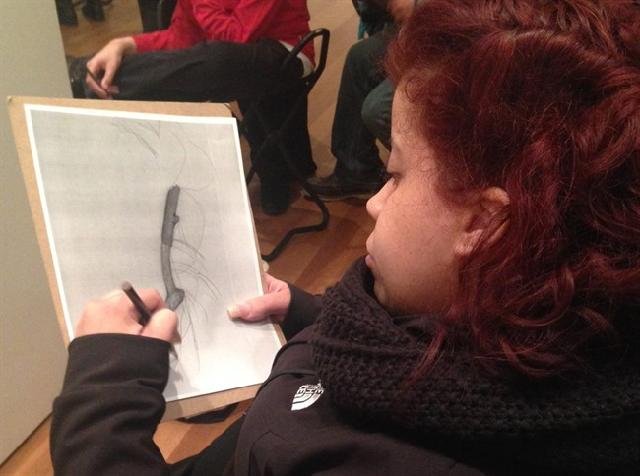

In this March 22, 2015 photo, Luz Cantres works on a drawing at the Museum of Modern Art in New York after viewing a sculpture by French artist Jean Dubuffet. Cantres was participating in "Create Ability," a program for individuals with learning and developmental disabilities. Each month participants in the MoMA program explore a different theme through an exploration of the museum’s galleries and art-making workshops. (AP Photo/Ula Ilnytzky)

NEW YORK, N.Y. - On a recent Sunday, a group of museum visitors sat in front of a large canvas by the French artist Jean Dubuffet as their guide described the work — an abstract painting created with crumpled aluminum foil tinted with oil paint.

The guide then invited them to create their own artwork using tin foil — a task the group enthusiastically embraced, creating an array of three-dimensional sculptures. The group was participating in a program at the Museum of Modern Art called "Create Ability" for people with learning and developmental disabilities.

It is one of many programs the museum offers to engage audiences with disabilities, including those with mobility, hearing and visual impairments.

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act, which prohibits discrimination based on an individual's disability and requires that facilities, including museum exhibitions, be readily accessible and usable to them. A Census Bureau survey found 12 per cent of the U.S. population, or 39 million people, had a disability in 2013 — a number expected to grow due to aging baby boomers. Since 1990, the breadth and scope of cultural arts programming for individuals with disabilities has greatly expanded and can be found at museums large and small.

For example, the Frost Art Museum in Miami last week held a daylong event for families with children with special needs that featured wheelchairs with attachments for painting on large-scale blank canvases and other art-making adaptive tools. The aim of such programs is to help children develop motor skills, concentration, social interaction and self-esteem.

Those kinds of skills were in full view at MoMA during the art-making component of "Create Ability."

Samuel Desiderio took great pleasure in sharing his creation of pebbles, sticks and sand with the others.

The program is "another avenue for them to share who they are," said Sharon McCann, the 28-year-old's home tutor who accompanied him to the museum.

Many cultural institutions have offered some level of accessibility programming long before the ADA became law. Today, many go above and beyond compliance. Touch tours for people with low vision, programs for children on the autism spectrum and assisted listening systems for the hearing-impaired can be found at many museums. Museum websites often feature virtual tours of their collections and allow blind people to navigate the sites via screen readers.

Among the biggest milestones in the past 25 years is the availability of audio descriptions presented by guides trained to vividly convey an image for the visually impaired via a recorded device or special tour. Additionally, some museums are equipped with a "loop," an assisted listening device. It's a copper wire embedded usually around exhibitions featuring an audio component. All a person has to do is turn a switch on their own ear piece and the sound is amplified — without anyone else knowing they have a disability or using the system.

"When you make accommodations for people with disabilities, you're better serving everyone." said Francesca Rosenberg, MoMA's director of community and access programs. For instance, museum officials discovered that sighted people also were listening to the audio guide that was specially designed and developed for the visually impaired.

People with dementia or children on the autism spectrum benefit from less crowded galleries or by attending special exhibitions but most people with disabilities enjoy touring the galleries alongside other visitors. Blind people, for example, "like to eavesdrop on what other patrons are saying about a work of art," said Rosenberg. "That's an important component of the program because most people with disabilities don't want to be singled out and separated."

Luz Cantres, 32, who has spina bifida, loved "the Create Ability" program.

"I'm trying to copy what I see but letting it flow," she said of a totem-like twig sculpture by Dubuffet.

Art shows her "it's not about fitting in but standing out and recreating yourself."